Updated at 5 p.m.

Last year, Xzavier Beamon spent three months incarcerated in the House of Correction — a Northeast Philly prison so decayed that the city has decided to shut it down.

Officials announced Wednesday morning they would relocate the 199 inmates currently living there and mothball the facility by 2020. Built in 1927, House of Correction is the oldest functioning prison in Philly, and it was widely known to be in horrific condition.

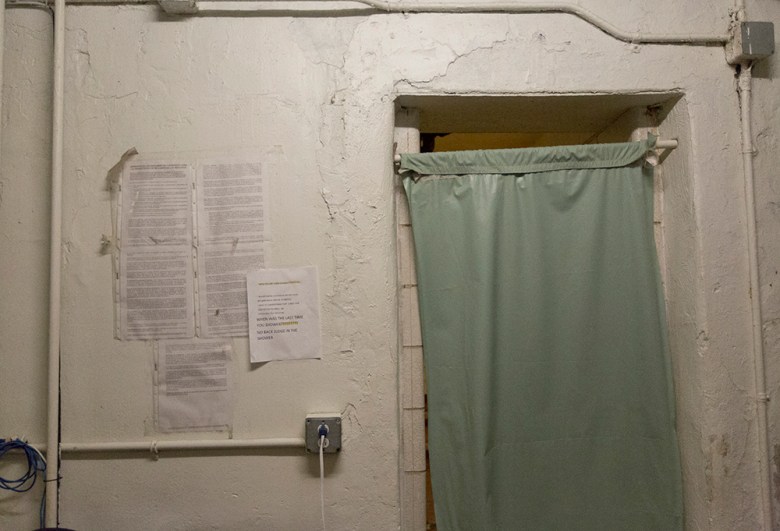

Beamon, 19, said paint regularly peeled off the walls, and exposed pipes leaked water onto the floors whenever someone flushed a toilet. The cells were freezing in the winter and scorching hot in the summer. No matter the weather, the walls and the air were moist — so much so that Beamon’s shoes and bed sheets grew mold.

“Sometimes in the morning when we turned on our water, it would taste like salt and metal,” Beamon said. “We would have to let our water run anywhere between five minutes to an hour just for it to taste normal.”

It was nearly six months ago that activists began their #CLOSETheCreek campaign to shutter the facility. This week, part of that effort appears to have paid off. Officials cited the facility’s age and worsening condition — as well as Philly’s decreasing prison population — as reasons for the closure.

However, many activists and formerly incarcerated people argue, the city isn’t going far enough.

Per Prisons Commissioner Blanche Carney, the city will continue to maintain the House of Corrections building even after removing all its occupants. If the prison population rises again, Carney said, the city could use the facility in the future.

But that logic is flawed, according to anti-incarceration activists. Reuben Jones, the #CLOSETheCreek campaign coordinator for Just Leadership USA, said it doesn’t make sense to preserve the building for future use if the city has already determined that it’s worth closing.

Jones wants the city to close the prison before its goal of 2020 — and then demolish it completely.

“Don’t maintain an old, dilapidated building for future use,” Jones said. “It’s inhumane to put people in living conditions like that inside a prison.”

Germel McClure, 24, was locked up at the House of Correction last Thanksgiving. It was “horrifying,” McClure said. “You don’t stick human beings in that situation.”

McClure is glad Philly decided to shutter the prison — but he’s disappointed the city plans to maintain the building. Locking people up in there again would be “inhumane,” he said.

“You’re taking people out of a bad situation and sticking them back in that bad situation,” he said. “These guys are living like barbarians.”

For Jones, the cause hits close to home. He spent 15 years of his life behind bars — including a stint inside Holmesburg Prison. The conditions there were similarly bad until the city closed that prison in 1995.

But since then, Philly has used the prison during times of overcrowding and for big events, like the Democratic National Convention in 2016.

It makes Jones sick to his stomach knowing that people could still be sent to Holmesburg Prison after he witnessed firsthand the terrible conditions. That’s what he’s trying to prevent at the House of Correction.

“If you want to announce a closure of a jail, then close the jail, period,” Jones said. “If the mayor is committing to closing the jail, then we want to see the jail actually closed and not used again.”

Activists will start an official campaign to demolish the prison with a rally outside City Hall on April 25 — exactly one week after the city’s initial announcement.

For several of the inmates who lived there, they hope the activism makes a difference.

“Living there, it’s all a terrible experience. There’s not just one thing you can pinpoint,” McClure said. “Nobody belongs on State Road.”